Fact and fiction

There’s an image of remote places in the general public’s minds, formed by direct experience and many third-hand reports, the media, misconceptions and prejudice. In the best case, this can give you an incomplete or misleading idea of a place, its people, their life and their culture, other times a completely wrong one. To me, the only way to find out what life is like somewhere else is to travel there and see for myself – as good as I can in the time available. Never has this been more true and eye-opening than during my trip to Iran.

The image many people have of Iran is that of a profoundly conservative, Islamic republic: Women completely hiding their faces, extremist leaders trying to build nuclear bombs, strict laws and executions. On top of that, you can add every other stereotype you’ve ever heard about Islam or Islamic extremism because for many the Middle East is a blur and distinguishing between the different countries and regions doesn’t happen as much as it should.

Yes, Iran is an Islamic Republic, with both a religious leader and a more or less democratically elected parliament. Part of the people not just adhere to the Islamic laws this comes with, but agree with them and support reserved relationships with the west. “Death to the USA” isn’t always just a remnant of the past.

There’s another side, though. A lot of people have different views on life, religion and politics. You’ll see women continuosly pushing the boundaries of the Islamic dress code with thin, beautifully coloured and designed hijabs barely covering much of their hair, let alone their make-up-covered faces. Especially in Tehran, like in any other large metropolis, you’ll find modern, open-minded young people. And yes, there are parties, alcohol and drugs – it just doesn’t happen publicly. And no, I didn’t feel the urge to try any of the above. I rather enjoyed a sober trip and experienced life as a traveller in an alcohol-free environment. It’s hard to describe, but it changes the atmosphere of a place, in my opinion, for the better. Without any particular reason, one thing still lasting from my trip (now several weeks ago) is not drinking any alcohol.

The ratio between traditional and progressive tendencies is hard to tell. So is, whether the country will see a shift in any of the two directions. Iran is on a path to continue to “open up”, but a more traditional and conservative government could also move the country in the opposite direction again. Either way, it’s essential to acknowledge that both views exist throughout society, and this ambiguity is a fascinating and essential point in understanding the country.

Wherever I visit in Iran, I meet friendly and incredibly hospitable people. Everyone is genuinely interested in my story. “Where are you from? (Don’t even try to say Austria, it’ll be understood as Australia 99.9% of the time. I go for “Otrish” (like the French “Autriche”: “Man otrishi hastam”.) What’s your name? Nice to meet you! What do you do? How old are you?” And the most important question of all: “How do you like Iran?” Hospitality is a cornerstone of Persian culture. As a foreign traveller you can almost be sure people will go to extreme lengths to ensure you’re having a good time – “and please tell your people at home how it really is”. Iranians are proud of their heritage and (rightly) concerned about how the rest of the world presents their country in the media.

The smoggy air of Tehran

My trip starts in Tehran. Most international flights arrive very late at night and mine was no exception. It gets almost 5 am before I clear immigration (very fast), exchange some money (even faster), grab a taxi (no problem) and check into my hostel (we’ll do that tomorrow, here is your room). These first two nights is everything that I’ve booked in advance besides the return flight. There’s a fridge full of water bottles and alcohol-free malt drinks in the common area. A box next to it kindly asks you to put in the money for every drink you take. It’s encouraging to see a trust-based system work. After some time in the country, you wonder why anyone would ever organize it differently. The mineral water brand is called “Damavand”, the name of the mystic Persian mountain, which has been my initial motivation to visit the country and shall follow me for the rest of my stay.

Rewind to two and a half years ago. I am 29 and thinking of a small “adventure” for my 30th birthday. Kilimanjaro comes to mind, but that is what “everyone does”, so I look into alternatives. I find a guided tour to the summit of Damavand and am immediately captivated. It’s the initial motivation to go to Iran, but the more I inform myself, the more I get intrigued by everything else about the country. While it’s questionable how much a guided tour walking up a mountain still counts as an adventure, I quickly decide to book it. A few weeks later, the organizers inform me that there are not enough people to make the trip happen. I have no time during the other dates, so I hike some Austrian mountains instead. Next year, the same story. Then I decide – after I’ve met an Iranian couchsurfer in Salzburg and have read quite a bit about the country and its history in the meantime – that if I ever go there, I’ll do it on my own.

On my second day in Iran (which is technically still the first after arriving long after midnight) I meet with an Iranian couchsurfer. She wanted to meet in Salzburg some time ago, it didn’t work out then, but she invited me to meet whenever I’d be in Tehran (“Now it’s my turn to say: let me know”). We walk around the streets of the capital, the heavy smog of leaded fuel in our noses, visit Azadi square at night (Azadi = freedom in Farsi, remember that for your shot at “Who Wants To Be A Millionaire”) and soon make plans on how to make my Damavand climb possible. I cannot thank my friend enough for realizing this is important to me and offering support in ways I would’ve never dared to ask for (and apologizing in the process, that she cannot do more). It has to wait a couple of days though, so I escape the smog the next day and take the bus to Isfahan.

All these colours – the beauty of Isfahan

The bus is pretty comfortable with Persian carpets on the floor and seats reclining almost all the way back. It still feels like an endless journey followed by an hour-long taxi ride across Isfahan’s nightly traffic. The “hostel” is a pleasant surprise. Like many places in Iran, it turns out to be a hotel selling some of its rooms as hostel beds at different rates. “Maybe another traveller will come to share the room with you”, but nobody ever comes, so I have the place all to myself.

The next morning I have my first Iranian breakfast. The hotel manager offers to take a couple of pictures of me in front of the beautiful ornaments on the restaurant walls. He gives me a friendly tap on the back. “Welcome to Isfahan”.

I soon make my way to the close-by Jameh mosque and on to Naqsh-E Jahan square. The buildings and bazaars still leave me breathless to this day and are among the most stunning impressions on my trip. One of my favourite stories occurs at the mosque. In the cool shadow under a tree in the patio sits an Islamic teacher welcoming travellers for free talks, cookies, tea and discussion. He speaks in a calm voice in fluent English and French answering with an ever-friendly face, what must have been the same questions day in and out. What’s the role of women in Iran (all women visitors ask that)? What’s Islam’s view of other religions (I ask that)? Many of the questions are already suggesting Islamic society would be mistreating women, and the imam does his best to counter the arguments, sometimes more sometimes less convincingly. Overall, I’m very impressed by the time I spend here. My bottom line is that, if people treated each other’s religion with more respect (which most religious teachings explicitly ask for), the world would be a better place today.

An American woman starts one of the discussion by bringing up Islamic inheritance law and how it prefers men to women. The imam’s counter-argument goes something like this: a man will marry and bring his money into the family, so in the end, everyone will benefit. The next question is, but what, if the woman doesn’t get married. The imam then goes to lengths talking about the importance of family in Islamic culture and how the law – while respecting minorities – is tailored to fit the majority and the role model of a family-based society. A while later, the women has already left, and some other guest asks me how old I was. In Iran, that’s a common question, usually thrown in somewhere between “Where are you from?” and “What’s your name?”. After telling him, everyone in the round goes like “No way, you look much younger!” and before I can even begin to feel flattered, the imam hit it by saying: “It must be because you’re not married. – Because one year of marriage is like four or five years”. This comes from the person talking about the importance of family for the last half hour. I still don’t know if he wants to win me over with a joke or end the topic on a lighter note, but it’ll make me remember this encounter for a long time.

I continue my way to the centre of Isfahan, having an excellent lunch in a rooftop restaurant. In the afternoon I take a taxi to Soffeh park and spontaneously hike to the 2257 m high summit. My hiking boots are still in Tehran, so I do the climb in my Converse sneakers, which is no problem on the way up, but requires extra carefulness on the descent. I meet some new friends from Baghdad while taking the cable car back down the mountain, flag another taxi downtown and call it a day.

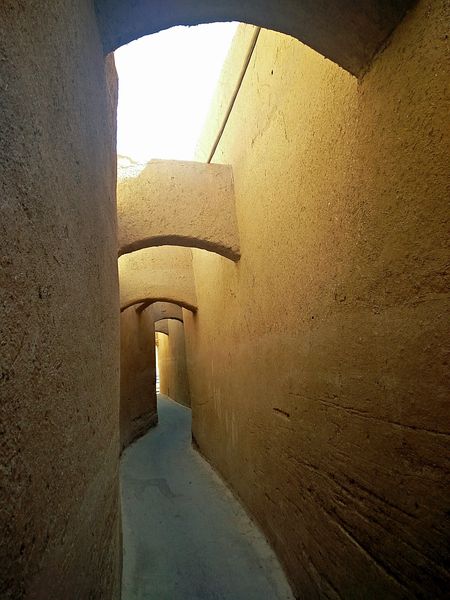

A glimpse of the desert – Yazd

The next logical step on the classic Iranian tourist itinerary would have been Shiraz, but the only way to get there from Isfahan is another hour-long bus ride. I opt for a train and go to beautiful Yazd instead. I meet a couple from Amsterdam at the train station, and we discover that the hotel they’re staying at is very close to the hostel I have booked. They have a free pick up service, and I just hop on and in the end (surprise, surprise) their hotel and my hostel were the same beautiful adobe building with a great common area in the patio and a rooftop restaurant with a gorgeous view. I spend the evening with another group of Dutch travellers, who teach me a simple card game. It either requires lots of experience or more tactical thinking than my brain is willing to do on vacation, I loose badly.

The next day I do, what seems to be the natural thing to do in a desert town. Explore in the morning, find a cool place to have a siesta during the day and go back out in the evening. I miss the opportunity to go to the desert for sunset, but having a day of relaxation and reflection is equally welcome.

Damavand

After the bus and train, the only means of transport left is flying, so with my Couchsurfing friend’s help, I book myself a flight back to Tehran. There are some safety concerns with domestic flights, but I think they are overrated. I regret not trying harder (or at all) to get a window seat. Domestic flights mostly land at Mehrabad (instead of the bigger Iman Khomeini airport), situated closer to the city. The final approach above the skyline of Tehran was quite an experience.

In the meantime, a plan for my Damavand hike has materialized. The father of a friend of my Couchsurfing host has climbed the mountain many times and insists on meeting us one early morning (5:30). He drives us to the start of the climb in Polour (Camp 1), about one and a half hours northeast of Tehran. He arranges my permit and a few minutes later I find myself on the back of a truck with a dozen Iranian climbers hauling up a bumpy mountain road to Camp 2 at 2900 m. From here it’s a 4-hour walk up to Camp 3 at 4200 m always forcing myself to go slow and take my time. The highest, I’ve climbed before, is Mauna Loa on Hawaii. Its summit is about the same altitude as Camp 3, and my only thought upon reaching it has been to go straight back down. Of course, I feel the thin air on Damavand as well, but it’s not as bad as expected. I have a good nap and hike up to around 4500 m in the evening feeling only slightly dizzy afterwards. I’ve no idea if I could manage the summit the next day, but I’m determined to give it a try.

Camp 3 is a concrete mountain hut with a small canteen and fresh water supply from a well. It’s the Iranian weekend, so the place is packed. People sleep in beds, on the floor, between the tables and everywhere, they find space (and that doesn’t even count the hundreds of tents spread all around the area). I wouldn’t have any chance on my own, but my couchsurfing host manages to organize me a bed. The trick is to identify the beds of the climbers, who are currently on their push for the summit. Chances are they’ll leave as soon as they come back and you’ll be in pole position for their beds.

You might think it’d be hard to find rest in a noisy environment, but it’s the best and deepest sleep in a long time. Maybe it’s the exhaustion, perhaps the sleeping pills. It sure helps getting acclimatized to the thin air. Shortly after 5:30 am, I start my hike. It’s cold until sunrise but soon turns into a beautiful day of hiking. I may have started alone, but there are dozens of other climbers to follow. An Iranian couple offers to join them to the summit. I also get offered so much food that I don’t finish half of what I’ve brought myself. Of course, I’m sharing that as well.

My new friends have a good pace, maybe a bit faster than what I would’ve done on my own, to make sure not to over-pace. After a while, we meet a friend of theirs, whose husband “abandoned” her during his summit push. We integrate her into our group, and a bit later also find the husband, already on his way back down. He turns around and begins to ascend a second time with us. That’s how the hiking groups grow. I’ve no problems with the altitude, but after a while feel, I should ascend faster to limit the time spent above 5000 meters. So I abandoned my group and push to the summit alone. Less than an hour later, I find myself on top of Persia at 5610 m. The official altitude, which is also very prominently displayed at a giant poster on the wall of Camp 3, is 5671 m, so I don’t realize how close I’ve been until I’m just below the summit, which almost comes as a surprise. I find some alone-time on a rock above the summit photo spot and enjoy the unbelievable view. Upon climbing down, I find myself being asked for photos and selfies by almost all the local climbers up there. I also meet the two guys, who’ve sat next to me on the truck the day before. They happen to reach the summit at the same time and eagerly greet me. It’s an atmosphere of happiness and achievement, and I make many new friends.

The most challenging part is the descent from the thin, clear mountain air down to Tehran’s thicker (albeit polluted) air. First, I head down to Camp 3, where I nap for two hours (big mistake), then to Camp 2 (which is somewhat challenging after waking up) and then by truck down to Camp 1 where another Iranian group offers us a ride back to Tehran. After standing on top of Damavand (5610 m) at noon, I return to Tajrish (1612 m), my favourite part of Tehran on the same day. I sleep like the dead again.

I spend most of the next day recovering, walking around Tajrish and finding the last presents and postcards for my friends and family back home. I feel exhausted in the afternoon, but after some “special tea” in a bookshop (I’m not sure, but I think it’s bitter orange leaves, damask rose and chamomile) I suddenly have enough energy to enjoy my last night in Iran.

Ten days is a short time, but I’m more than happy to have taken the opportunity. There’s a lot more to see: the Northern part (maybe climbing Damavand from the other side), the sunset in the desert, Shiraz, Hormoz Island in the south and also lots of places to visit again. It’s always a struggle to decide whether to go back to a country you’ve enjoyed visiting or instead go somewhere new. Still, Iran is high up on the “places I want to see again” list – for nature, the history, the culture but mostly for its people.